Silong, Cambodia

Silong was born in the Battambang province, in Cambodia. He is not sure exactly where, as he was born during the Cambodia civil war. His dad was a soldier for the opposition army and had to flee as soon as the war started to avoid persecution. Seen as guilty by association, and wanting to be with her husband, Silong’s mom fled when he was just an infant to a refugee camp to Thailand. She hired some help to carry Silong and reach the camp in Chonburi hiking through mountains and forest, dodging Khmer and Vietnamese soldiers and landmines. Indonesia was a stepping stone to apply for asylum in the U.S. under the United States Refugee Act of 1980 (Public Law 96-212), signed by President Jimmy Carter, which created a methodical and lasting procedures for refugees to settle in the U.S. This amendment, following the controversial and disastrous Vietnam War, allowed for the biggest wave of south East Asian to date[1]. The family stayed in the camp for two years waiting for the paperwork to come through. As a baby Silong was malnourished because his mom had an infection and could not breastfeed him and the life in the camp was not easy. Finally, after two years the family was allowed in the U.S., through New York, and briefly San Francisco, they settled in Tacoma, where Silong’s paternal Aunt had escaped to just before the Khmer Rouge (Cambodian communist party) started ruling the country. She had sponsored her family to come join her.

Silong’s parents frequented Tacoma Community House, where he works now, for English classes and citizenship assistance and worked full time jobs. He did not speak English very well until 3rd grade and has ESL (English as a second language) classes, since they spoke Khmer at home. School was challenging and Silong found himself caught up in an identity crisis, and had to slowly find a balance between the two. When he was growing up many people in the community wanted to assimilate, several even changed their names to make it easier to blend in. Silong went to Lincon HS, where he discovered hip-hop, in particular New York City based Wu-Tang Clan, which resonated with him and inspired him to be more self-aware. In general Hip-Hop was the culture of the “have not” and encouraged to take what you have make nothing into something. It was troubling time in his South East Asian neighborhood, riddled with crime and gang activities: socioeconomic challenges, parents gone to work all day, in between culture and with no guidance, the kids sought validation, protection from being picked on and relied on gangs as surrogate families. Silong, who was keep under close watched by his parents, found music and skateboarding, as his main outlets, which build his confidence and self-esteem. After High School he got an Audio Production degree at the Art Institute of Seattle and he keeps working and living in Tacoma with his wife and kids.

Occupation: Digital Communication Manager for Pacific Lutheran University, former Communication Associate at Tacoma Community House

Family in the US: Mom (dad went back to Cambodia), siblings (born here) and extended family

Languages: Khmer and English

Favorite pastimes: playing music (Guitar, DJing) audio editing, recording and producing music

Favorite music: primarily hip hop and RNB, but many other types of music too

Could do without: Growing up in Tacoma Silong experienced bullying and micro aggression at school and beyond (anything from being asked if he was Chinese and ate dogs, to being called, on purpose, “shlong” (slang with a specific negative meaning) or “so long”) and he soon learned to brush it off, to learn how to not react to something that he couldn’t change (he said “I can control how I react not what they say. It’s like putting rainex on the windshield. It still rains but it doesn’t affect me as much. To quote Jay-Z “What you eat don’t make me shit.” Meaning one has to focus on oneself”). One episode in Nebraska recently did surprise him: Silong was in a fast-food with his boss (a white man) and ordered a shake. When his number was called and he approached the counter, the clerk refused to give it to him, handing it to his boss instead, and once he pointed out that Silong was right there waiting, she ultimately leaft it on the counter.

Still hard to say: nothing, English is his primary language

Favorite expressions: English “Never a failure, always a lesson”

Khmer:អ្នកមិនចាំបាច់កាត់ដើមឈើចោលដើម្បីទទួលបានផ្លែនោះទេ

(You don't have to cut a tree down to get at the fruit)

Objects:

-

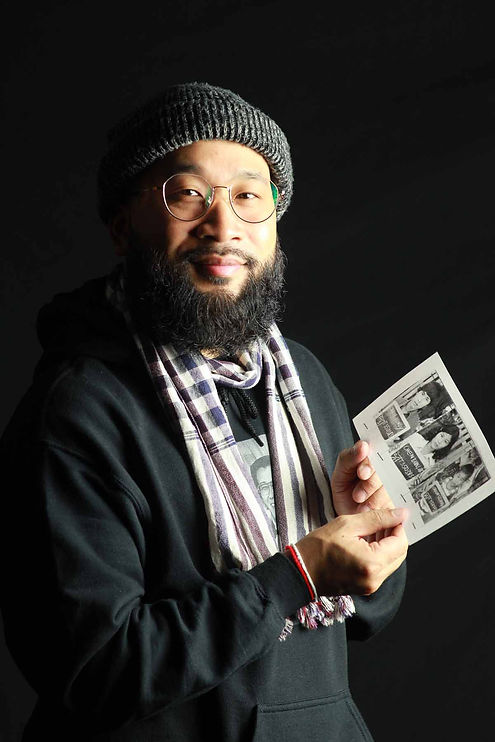

Krama: traditional Cambodian scarf used for a variety of purposes, from face mask, head scarf, to carrying a baby, is used for both fashion and function. In the Bokator martial art is used even as a weapon. During the Cambodian genocide, red scarf was used as symbol for Khmer Rouge party.

-

Haing S. Ngor Sweatshirt.: Created by Silong’s own t-shirt brand Red Scarf revolution, it sports the screen-printed photo of Haing S. Ngor, winner of the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor in 1985 for his debut performance in The Killing Fields, in which he portrayed Cambodian journalist and refugee Dith Pran. He is the only ever male actor to receive this award, and he experienced in real life the horrors occurring in Cambodia after the Khmer Rouge coup in 1975.

-

Photos of Silong and his parents: The asylum application documents submitted by Silong’s parents were accompanied by these three photos of the family holding a blackboard with their names and numbers identifying them as a family belonging together.

-

Blessed String bracelets (got in Angkor Wat, Cambodia): Buddhist blessed string bracelets part of the Buddhist culture are made of a cotton thread and are called “sai sin.” The sai sin is supposed to provide protection and good health to the person wearing it. It is typically a monk uttering prayers and blessing, who will tie the bracelets on the person’s wrist.

[1] “The makings of our modern resettlement system can be traced back to the fallout of the Vietnam War, a cascade of international crises stoked by the U.S. Starting in the mid-1970s, hundreds of thousands of “Indochinese” refugees poured out of Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia, escaping newly installed brutal communist governments, ethnic repression, retribution against American allies, starvation, war crimes, and genocide.” Seiff, Abby. “How the Vietnam War Shaped U.S. Immigration Policy.” JSTOR Daily. January 22, 2020. https://daily.jstor.org/how-the-vietnam-war-shaped-u-s-immigration-policy/